The writer Vladimir Nabokov, in a quiz to his students, once claimed that a “good reader” must have four things: imagination, memory, a dictionary, and an artistic sense. He added: “A book of fiction appeals first of all to the mind. The mind, the brain, the top of the tingling spine, is, or should be, the only instrument used upon a book.”

What happens when Perception Boxes don’t match? Can you still be one of Nabokov’s “good” readers?

Consider that, in 1951, one of Nabokov’s short stories, “The Vane Sisters”, was rejected by The New Yorker’s fiction editor at the time, Katherine White. He angrily wrote her a letter back claiming that the magazine had “not understood” his story. What she had seemingly not understood was that Nabokov had hidden an acrostic puzzle in the final paragraph which hinted at a hidden plot riddle. In his letter to The New Yorker, he explained the puzzle:

...the last paragraph which, if read straight, should convey that vague and sunny rebuke, but which for a more attentive reader contains the additional delight of a solved acrostic; I C-ould I-solate, C-onsciously, L-ittle. E-verything S-eemed B-lurred, Y-ellow-C-louded, Y-ielding N-othing T-angible...

Nabokov bristled at the rejection. Artists live in a Perception Box conundrum. Many pride themselves on seeing the world differently than others but then become wounded when their unique perspective is not understood or appreciated. The New Yorker editor, viewed from inside Nabokov’s perspective, was being a bad reader.

Why did Nabokov assume this acrostic would be so obvious to his editor or to any “more attentive” reader? We can presume Katherine White truly was an astute, attentive reader—after all, she was the magazine’s fiction editor.

Why didn’t she pick up on the puzzle that seemed so clear and obvious to Nabokov?

Because their different Perception Boxes made it so.

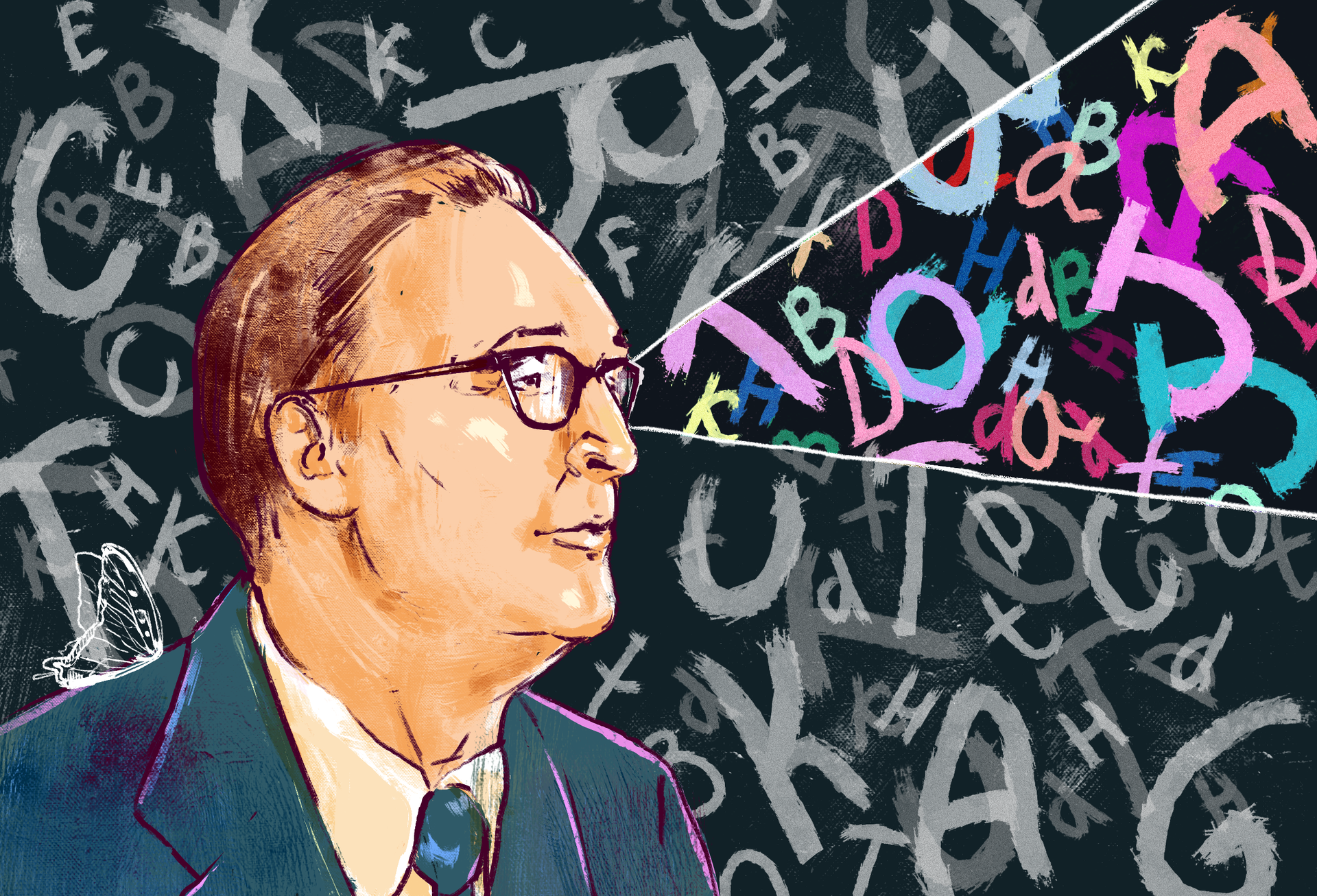

Nabokov was famously a color-grapheme synesthete. For him, certain letters of any written text appear reliably colored. Which means that, likely, at a basic perceptual level, Nabokov and the editor saw the very text which was printed on the page quite differently. For color-grapheme synesthetes, each letter and number is associated with a color.

According to Nabokov’s memoir, published the same year he wrote “The Vane Sisters”, both his wife and son shared the condition. However, the specific colors they experienced varied in the details. The letter ‘M’, for example, appeared pink to Vladimir, blue to Vera, his wife, and “purple, or perhaps mauve” to Dmitri, their son. (Remarkably, the exact same letter appeared as a different color for Vladmir whether it was part of an Roman, i.e. English, or Cyrillic, i.e. Russian, word.)

Was Nabokov’s disagreement with The New Yorker editor not at all about the taste or quality of the story? Was it due to unknown, misunderstood differences in their Perception Boxes?

It is near certain that Nabokov knew, on some level, when writing “The Vane Sisters” that he had a unique perceptual condition which most readers, and likely his editor, did not have. If so, the walls of Nabokov’s Perception Box were both wide and narrow. Wide in that he saw colors where others saw black and white; narrow in the sense that he had little patience for those who did not see the way he did.

For most stories, it doesn’t matter that a writer and his reader see the very text on the page differently. But for this particular story, with a letter-based puzzle, it may have been required. Maybe part of his angry reaction to her failure to see the puzzle was that he was trying to surprise and delight, but since she could not see what he saw, he failed to do so, which ultimately was a failure to connect. Which must have made him feel isolated and alone in his Perception Box. If only he’d been able to recognize the difficulty of his expectation!

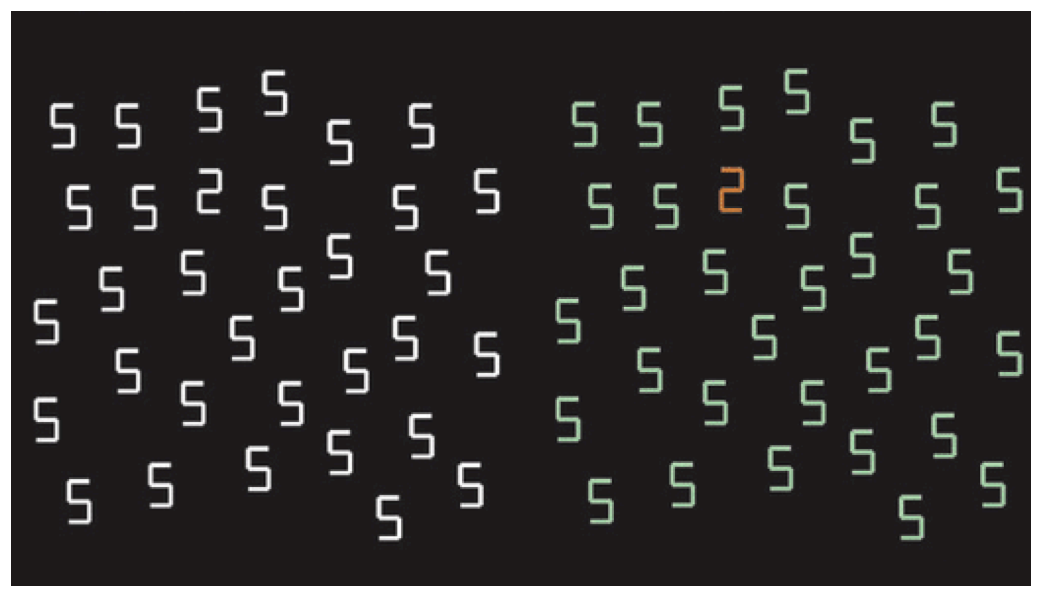

Consider the following pop-out where the goal is to spot the numeral ‘2’ as quickly as possible. Notice the exponential difference in challenge if all the numerals are in monochrome (left half) versus if the ‘2’ is a different color (right half) than its distractors:

At least one case has been reported where an adult man’s color-grapheme synesthesia seemed based on, get this, the Fisher Price magnetic alphabet toy he had as a child. As an adult, all but one letter of his synesthesia perfectly matched the Fischer Price toy set. (Likely, he was going to have synesthesia but the contours of his Perception Box were made as he played with the toy.)

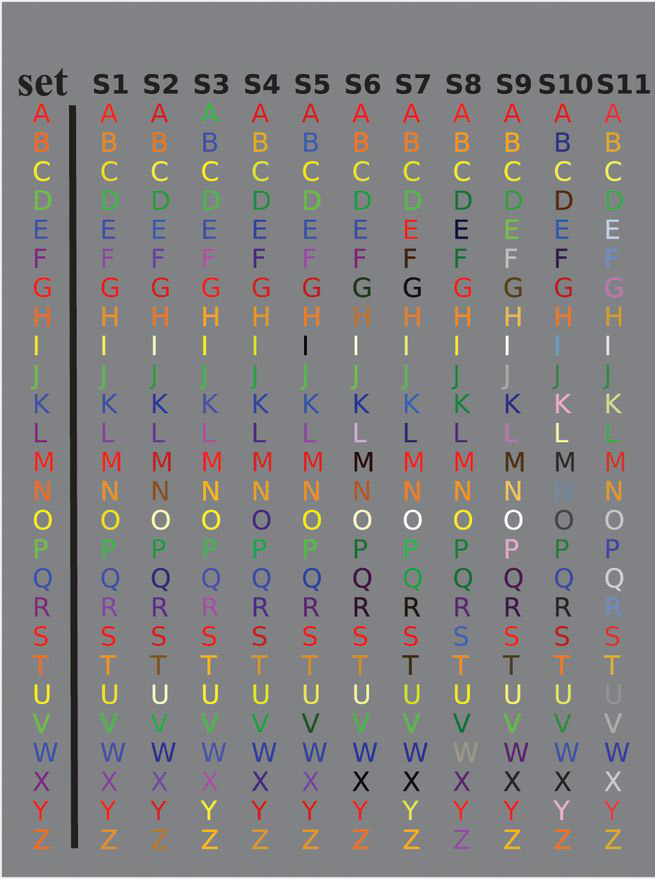

The study found ten other people whose colors were remarkably similar to the toy set, as seen in the image below. The leftmost column is the Fischer Price color alphabet. Each column is a different person and their subjective, Perception Box pairings of letters to colors:

Is a Fischer Price magnetic alphabet set, in fact, the secret fifth ingredient to being a Nabokovean “good reader”?

Perception Box Question

Have you ever been excited to share a discovery or creative work with someone else and they didn't like it or get it? How did that make you feel inside, and why do you think that is?